Approximately 8% percent of the adult population or more than 5.5 million people in the United Kingdom have gallstones. About 50,000 of these patients undergoing gallbladder surgery each year.

Approximately 8% percent of the adult population or more than 5.5 million people in the United Kingdom have gallstones. About 50,000 of these patients undergoing gallbladder surgery each year.

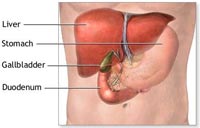

Gallstones (pictured rigth) are composed principally of cholesterol. Stones tend to grow for the first 2-3 years, at which point growth tends to stabilize; 85 percent of all gallstones are less than 2 cm in diameter. Most patients (about 80%) with gallstones remain symptom-free for many years and may, in fact, never develop symptoms. However, the consequences of gallstones may be severe, ranging from brief episodes of biliary pain to potentially life-threatening complications, such as acute infections of the gallbladder or pancreas.

Until the 1990s the prevailing surgical treatment of symptomatic gallstones was an open operation through an abdominal incision to remove the gallbladder. However, because of the pain associated with the large incision patients invariably stayed in hospital for 5-7 days. Now it is accepted that the best treatment for symptomatic gallstones is removal of the gallbladder by keyhole surgery, termed laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

This technique requires that only a few small (about half-inch) incisions be made in the abdominal wall. The gallbladder is removed through one of the small incisions, the laparoscope and instruments are removed, and the incisions are closed with sutures and covered with small bandages.

The operation requires general anesthesia and is subject to the same risks and complications as open cholecystectomy. However, patients have little pain after the operation, and hospital stays (1-2 days) and recovery (1-2 weeks) are shorter than after open cholecystectomy.

- What are the complications of gallstones?

- Which Patients With Gallstones Should Be Treated?

- Which Patients With Gallstones Should Be Treated With Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy?

- Summary

What are the complications of gallstones?

Only 10% of patients with gallstones will experience symptoms. Gallstones that are confined to the gallbladder usually cause only intermittent episodes of pain, known as biliary colic – commonly occuring after eating a fatty meal. When a stone occludes the exit of the gallbladder the flow of biliary fluid becomes stagnant, predisposing to infection and inflammation of the gallbladder, called acute cholecystits. The patient may have a temperature, symptoms of more severe upper / right sided abdominal pain and may vomit.

When gallstones enter the common bile duct they can cause jaundice , cholangitis and pancreatitis

Jaundice is caused by the stone blocking the flow of bile into the duodenum. This leads to the absorption of bilirubin into the bloodstream causing yellow pigmentation of the skin and eyes.

In addition to a stone in the bile duct causing jaundice an infection in the biliary system, called cholangitis can occur. This is again caused by stagnant flow of bile. The infection can reach the liver if not treated appropriately, leading to severe inflammation of the liver and eventually to liver abscesses if not treated.

Pancreatitis can occur when a gallstone passing through the bile duct temporarily occludes the pancreatic duct leading to inflammation of the pancreas. The condition is usually self limiting and responds to analgesia and resting of the bowel. However in a small proportion of patients the pancreatic damage triggers a cascade of worsening inflammation leading to a severe critical illness.

Rarer complication of gallstones include perforation of the gallbladder, erosion of the gallbladder into bowel (cholecysto-enteral fistula) and passage of a gallstone into the bowel leading to bowel obstruction (gallstone ileus).

Which Patients With Gallstones Should Be Treated?

Once gallstone symptoms appear, they recur in the majority of patients. Most symptomatic patients should be treated. Pain from gallstones (‘biliary pain’) is often severe, episodic, lasting 1 to 5 hours, often waking the patient at night, and located above the bellybutton (‘epigastric’) or in the top right corner of the abdomen. Biliary pain often flares soon after eating. Nearly 90 percent of patients with typical biliary pain are rendered symptom free after successful treatment of their gallstones.

Once gallstone symptoms appear, they recur in the majority of patients. Most symptomatic patients should be treated. Pain from gallstones (‘biliary pain’) is often severe, episodic, lasting 1 to 5 hours, often waking the patient at night, and located above the bellybutton (‘epigastric’) or in the top right corner of the abdomen. Biliary pain often flares soon after eating. Nearly 90 percent of patients with typical biliary pain are rendered symptom free after successful treatment of their gallstones.

Which Patients With Gallstones Should Be Treated With Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy?

Since the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 1988, this procedure has become the gold standard for gallbladder removal. Most patients with symptomatic gallstones are candidates for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, if they are able to tolerate general anesthesia and have no serious cardiopulmonary diseases or other coexisting conditions that preclude operation.

Some patients with very serious complications from gallbladder disease may not be eligible for laparoscopic gallbladder removal. In addition, patients in the third trimester of pregnancy should not usually undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy, because of risk of damage to the uterus during the procedure.

Most patients with gallstones remain asymptomatic. Asymptomatic patients usually develop symptoms before they develop complications. Therefore, with few exceptions, patients with asymptomatic gallstones should not be treated.

Once gallstone symptoms appear, they tend to recur, and such patients are more prone to develop complications. Thus, most patients with typical biliary symptoms and gallstones should be treated.

Because gallstones are so prevalent, they are often present incidentally in patients with other diseases. Patients with gallstones and atypical pain or dyspepsia need further investigation to determine the cause of their symptoms.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy provides a safe and effective treatment for most patients with symptomatic gallstones. Indeed, it appears to have become the treatment of choice for many of these patients.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy provides distinct advantages over open cholecystectomy. It decreases pain and disability, without increasing mortality or overall morbidity.

The outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is influenced greatly by the training, experience, skill, and judgment of the surgeon performing the procedure.

Multimedia

Multimedia

Patient Forms

Patient Forms